Handling Pressure in Pandemic

The concept of actions economy and how to leverage it to build up tension

As a kid, did you ever invent custom rules to improve the board games you were gifted?

My brothers and I certainly did! Given the typical low-quality-dice-rolling games we had in the 90s, it wasn’t really hard to create fun variants. Matt Leacock had the same experience with his uncle, and this early passion eventually led him to invent a genre-defining board game, Pandemic.

When it came out in 2007, Pandemic was an immediate success. It was one of the few cooperative board games on the market and featured the unorthodox theme of a team of experts fighting against a globally spreading disease. Pandemic sprouted a new sub-genre sometimes called ”coop firefighting”, where players try to handle a situation that spins out of control.

How can you design a game to enable such emotions? The answer is careful attention to the concept of action economy.

Dallas, We’ve Running Out of Actions.

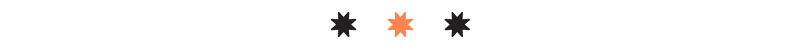

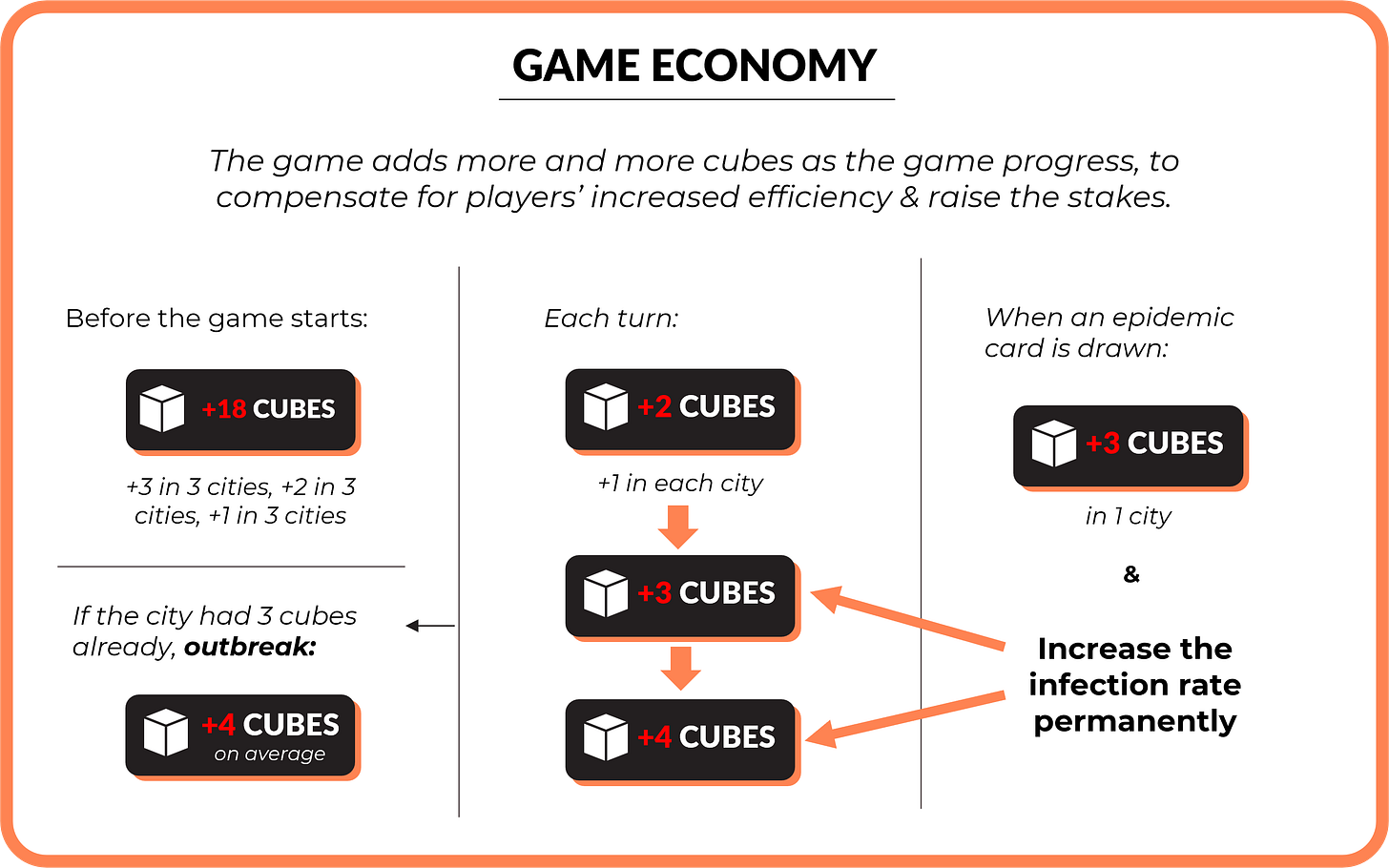

Pandemic’s danger is easy to grasp. At the end of each player’s turn, they draw “Infections cards” and place a cube on the mentioned cities to represent the disease. You lose immediately if you run out of cubes to place (there’s a limited number available). So, roughly speaking, the players’ goal is to try to remove cubes to avoid losing. Easy? Well, not really..

Running out of cubes is a rather distant threat (10+ turns), but there’s a more immediate one. Whenever you must put a cube on a city that already has three, an outbreak occurs and each connected city gets a cube too. Since each city is connected to four others (on average), you should avoid this situation (first because it adds many cubes, but also, you lose if you let eight outbreaks happen during a game).

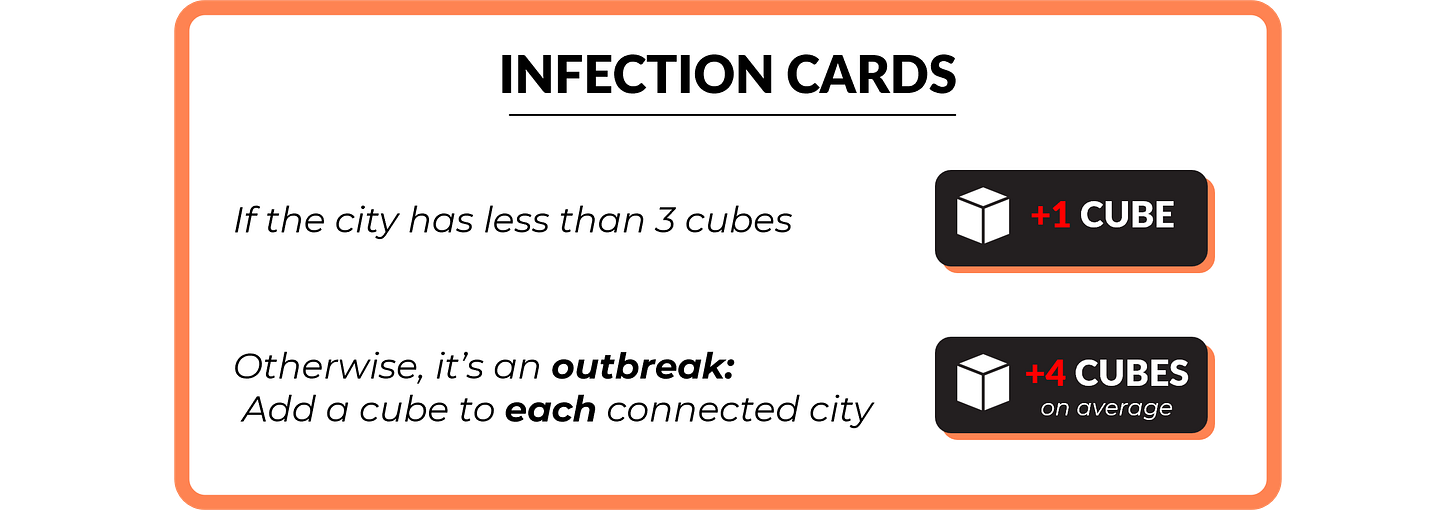

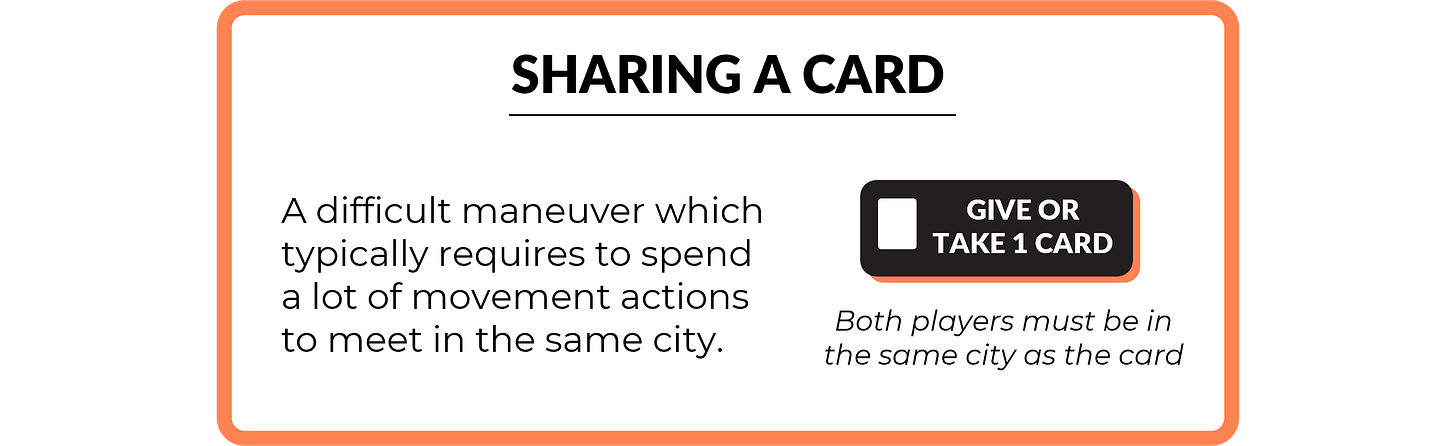

During their turn, each player gets four actions to spend how he wants. The most frequent are 1) moving their pawn to a connected city and 2) removing one cube from their city.

To contain the infection, you should ideally spend two of your four actions to remove a cube (and probably the other two to move where they are).

If we look at it from the other perspective, the game “asks” players to spend at least two actions each turn to compensate for the new cubes.

The strategy of a coop firefighting game is to figure out the most optimised ways to use your actions (as a group). You don’t want to have more cubes added to the board than you can remove. Hence the term “action economy”.

At first, the balance between “requested” & “available” actions is manageable, you have some margin, but as the game progress, the pressure keeps mounting.

Wasting Time & Winning Tempo

So far, we were merely avoiding loss, but how do you win? To save the world of Pandemic, you must find the cure for each disease, which is done by collecting five player cards of that disease’s colour and discarding them once in a research station.

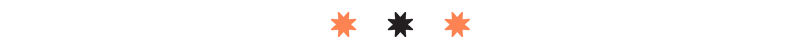

Discovering a cure is also a way to improve your efficiency: once a disease has a cure, it takes a single action to remove all cubes in your city (instead of one cube per action). So, discovering cures both brings you closer to winning and improves your action economy. Fantastic!*

*if you can survive long enough

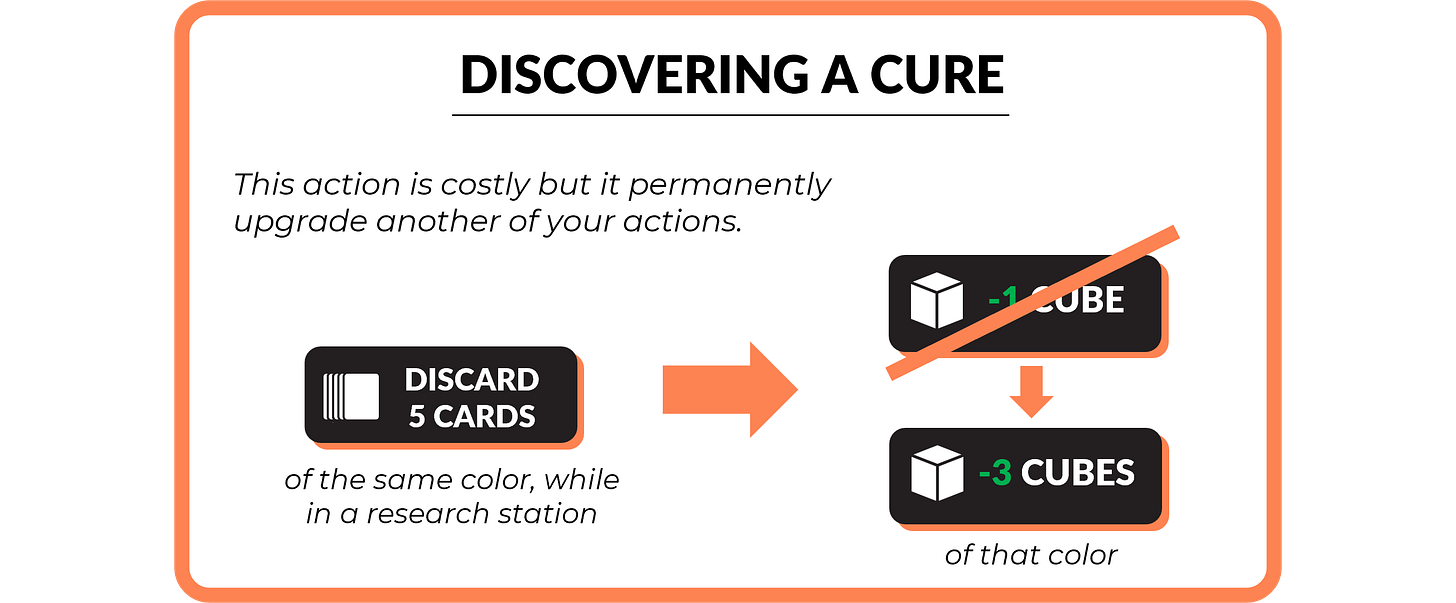

However, since you only draw two cards per turn, collecting five of one colour through sheer luck isn’t very likely. You typically need to rely on yet another action called “Share Knowledge” to trade with your partners. To perform this manoeuvre, two players need to meet in a city to exchange the card of that city.

It requires a lot of actions, and of course, you’re spending them to remove the cubes, therefore the pressure continues to mount.

On top of that, players are limited to seven cards maximum in their hands. This rule forces them to discard frequently, so they must make difficult choices to prioritise collections.

But, on the flip side, it also means that they may as well spend their cards voluntarily to accomplish one of these more efficient actions:

Discard a card to move directly to the mentioned city

Discard the card of the city you are currently in to go anywhere

Discard the card of the city you are currently in to build a research station

Stations can be both used to move faster (moving from a station to any other station counts as a single action) and to discover a cure (you must be in a station to discard the five cards). In the same vein as the Cure Discovery & the Knowledge Sharing, building a station doesn’t give an immediate advantage, but it increases your actions’ efficiency in the future.

In a nutshell, to win a game of Pandemic, the group must find the right balance between spending actions to control the immediate threat and “investing” actions to improve your odds of surviving (and eventually winning). In other words: you try to avoid losing now while working towards future victory.

Accelerating Threat

Do you remember that Pandemic is all about losing control of the situation? Well, the intention wouldn’t work if players could control every risk and improve their efficiency (which would make the game easier as it progresses).

To dynamism to the game, the designer had the brilliant idea to make you shuffle “Epidemic cards” at semi-regular intervals inside the deck. You’re in for an immediate adrenaline rush when you draw one of them!

First, you take an infection card and immediately add three cubes there! Second, you increase the “infection rate” (the number of infection cards drawn each turn). As you’ve understood by now, it means the game now “demands” more actions each turn to control the threat.

Third, and that’s another genius idea from Matt Leacock, you shuffle all the infection cards back on top of their deck: meaning that during a game, the same cities keep coming back. This mechanic increases the likelihood of triggering outbreaks, including in the city where you just added three cubes: you must immediately rush there to contain the epidemic!

The mechanic is essential to the rhythm & tension of the game. Because of it, players can’t “play with fire” and let the board fill with cubes: they have to be proactive about the threat, take calculated risks, and be ready for the upcoming epidemic cards which will disrupt their plans and put them on the brink of disaster.

In design terms, the epidemic cards create sudden spikes in the number of “requested actions” while also permanently increase the rate. At some point, players are facing dilemmas: they don’t have enough actions to control all the threats and need to make risky moves to get a chance of winning—a clever game design which perfectly fits the game’s theme.

Wrap-Up

The concept of “actions economy” is easier to analyse on a board game, where there is a finite number of clearly-defined possibilities. Still, the learnings apply just as well to video games.

The closest equivalent to the coop firefighting genre would be survival, where players typically face many threats with limited time (before the night, for instance) & resources. In games such as Don’t Starve, you get more efficient at surviving over time, but the game is simultaneously ramping up the difficulty of threats it sends you.

Give the player a little more to do they can comfortably manage and observe how much fun they get when they inevitably lose control.

If you liked the topic of this article, I’m sure you’d also enjoy this one: