The Last of Us Perfect Story Design

A look at the intrinsic narrative qualities that money can’t buy.

Narration feels like witchcraft for many game developers (myself included).

Unlike other disciplines, the story creation process isn’t well known, probably because there are many notions & methods you may use to write an engaging narrative. The typical game review stays on surface, giving a summary of the plot & throwing adjectives at the characters (what are we supposed to understand when they say someone is “memorable” or “forgettable”?).

As a game designer, I consider myself a scientific person: I have a rational approach to systems, components & rules and always attempt to analyse how & why they work (or don’t) within a given game. The Last of Us became an instant personal favourite since its release, yet I struggled to really nail what made this game so great beyond the “obvious reasons” (outstanding actors, unusual themes, cinematographic realisation, etc.)

I’m far from perfectly understanding the game’s narration and even further from writing one myself, but I’ve now got a clearer picture of the intrinsic qualities of The Last of Us. It all started with a book...

Robert McKee’s Story formula

Throughout this article, I’ll repeatedly refer to the same book to explain critical concepts: Story by Robert McKee. I didn’t pick it randomly: Neil Druckman, creative director & writer of The Last of Us, has explained on several occasions how influential this particular storytelling book was for him & the Naughty Dog studio.

Breaking down a story into individual components can help us understand what makes them engaging. However, remember there’s no magic here: even with a model, it takes a lot of creativity & iterations to reach a high-quality story. It worked for Naughty Dog, so let’s learn from the best!

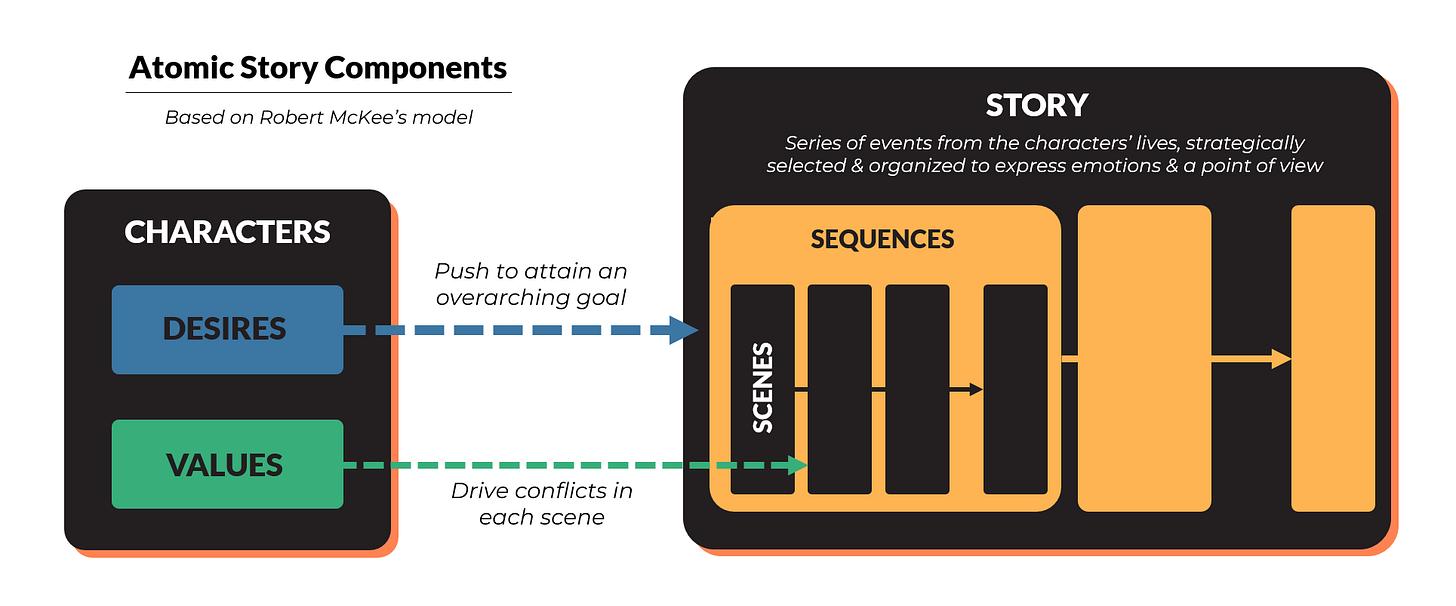

In Robert’s McKee model (simplified for this article), each important character has desires and values that shape their perception of the world.

Throughout the plot, we see them in scenes (40-60 in an average movie) where the different values are opposed to create conflict.

Several scenes are stitched together to form sequences with higher stakes & climaxes. Ultimately, the story can be seen as a series of events from the characters’ lives that are strategically selected & organised by the author to express a point of view & deliver emotions.

That may not sound particularly helpful or innovative so far, but let’s dig into the concrete example of The Last of Us.

Dimensional Characters: Desires & Values

The Last of Us main protagonist is Joel and he’s introduced as a protective father during the prologue, set on outbreak day, then re-introduced twenty years later as a stone-heart smuggler in Boston’s quarantine zone. This two-part exposition is crucial to present to the audience Joel’s dimensions, which, to McKee, are the character’s contradictions that make them nuanced.

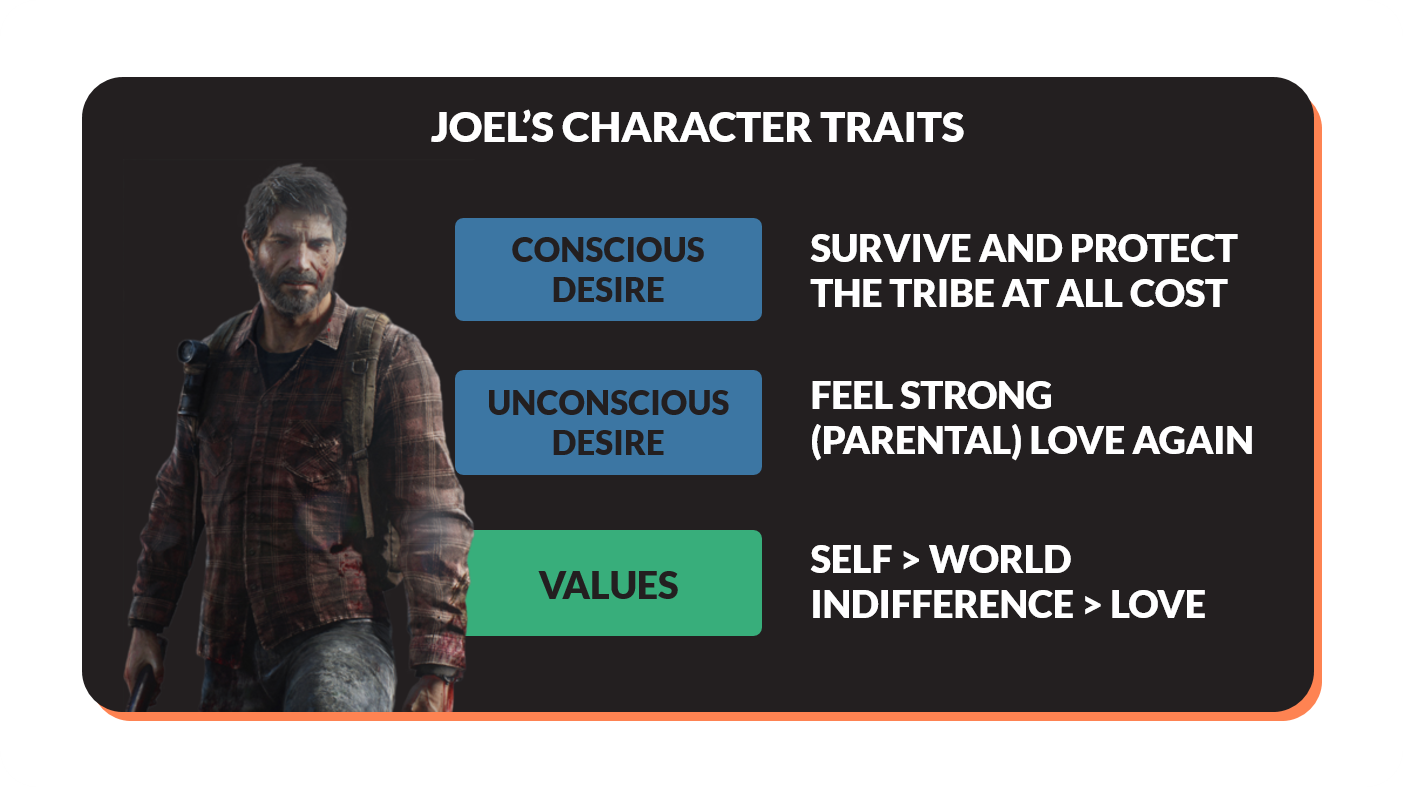

Protagonists are driven both by a conscious & an unconscious desire, which are typically conflicting. Joel’s conscious desire is to survive and protect his tribe at all costs (as seen with Sarah, then with Tess), but his unconscious desire is to experience a parent-daughter relationship again.

At first, he’s sticking to his concrete goal “deliver the girl to get my smuggled weapons back”, but as he fails to accomplish this task, he gets deeper and deeper towards the place he never wanted to return: the fear of losing the loved one.

The character’s motivations & internal struggles are explicit right from the start, we develop empathy without a word. The prologue could never have been a flashback after the fact, (not that Naughty Dog dislikes them, it worked to tell Ellie’s story), but because we need to understand intuitively where the story goes. After seeing Joel capable of loving his daughter, we wonder if/when he’ll return to that point.

On a fundamental level, Robert McKee also explains that the story’s emotions, or as he calls them, the values, are dual (freedom & slavery, life & death, hope & despair). The character’s arch is therefore a slow change from one to the other, as their view of the world gets challenged by the events & other characters.

Joel’s main characteristic is indifference when the story begins (yes, The Last of Us inciting event is Joel meeting Ellie, not the outbreak or the death of Sarah)—the opposite of love.

A classic mistake in storytelling, and particularly in video games, that Naughty Dog avoided there, is to use values that are contrary instead of contradictory. Contrary values such as “love & hate” or “good & evil” accept in-betweens compromises, and changing from one to the other feel cheap & forced (you don’t go easily from ‘hate’ to ‘love’, but you may become ‘acceptant’)

Another mistake would be to have a single value driving the character: each choice becomes so obvious that it’ll be difficult to generate tension & drama. Imagine if Joel was egoistic rather than a protector: he’d abandon Ellie on the first occasion, and the story wouldn’t work. Instead, we have a nuanced character who faces difficult choices and whose values oppose the other characters. His cynism contrasts with Ellie’s innocence and hope.

Each character in the story has a different viewpoint, with no clear right or wrong, an essential setup to generate the “currency” of a good story: conflict.

Layers of Conflicts & Intense Scenes

Indeed, all those rich & subtle characters would go to waste if they didn’t experience situations which reveal their values to the audience and challenge them. We don’t want the writer to simply tell us the struggle through dialogue, we need to see it in action.

Those “forces of antagonism”, as McKee calls them, can pressure the protagonist on several levels: the inner conflict (that we’ve discussed already in Joel’s case), the personal conflicts between characters and extra-personal conflicts (against the threat of nature).

In video games, the latest tends to receive a lot more attention since it provides obstacles for the character, and The Last of Us is no exception with its violent post-apocalypse setting. The game doesn’t stop there, however, as it expertly weaves the layers of conflicts together: Ellie being immune & a potential cure for humanity plays a significant role in the narrative but it’s also a tool to push the tension between characters, and in turn, affect Joel’s inner conflict.

The events (or scenes) have increasing stakes that shake the balance of the protagonist, who struggles to find a new equilibrium. Change is slowly coming; thus, the narrative tension remains high. What keeps us riveted to our seats is the fate of the key characters: will they finally realise what we all guessed? Can they overcome their inner demons?

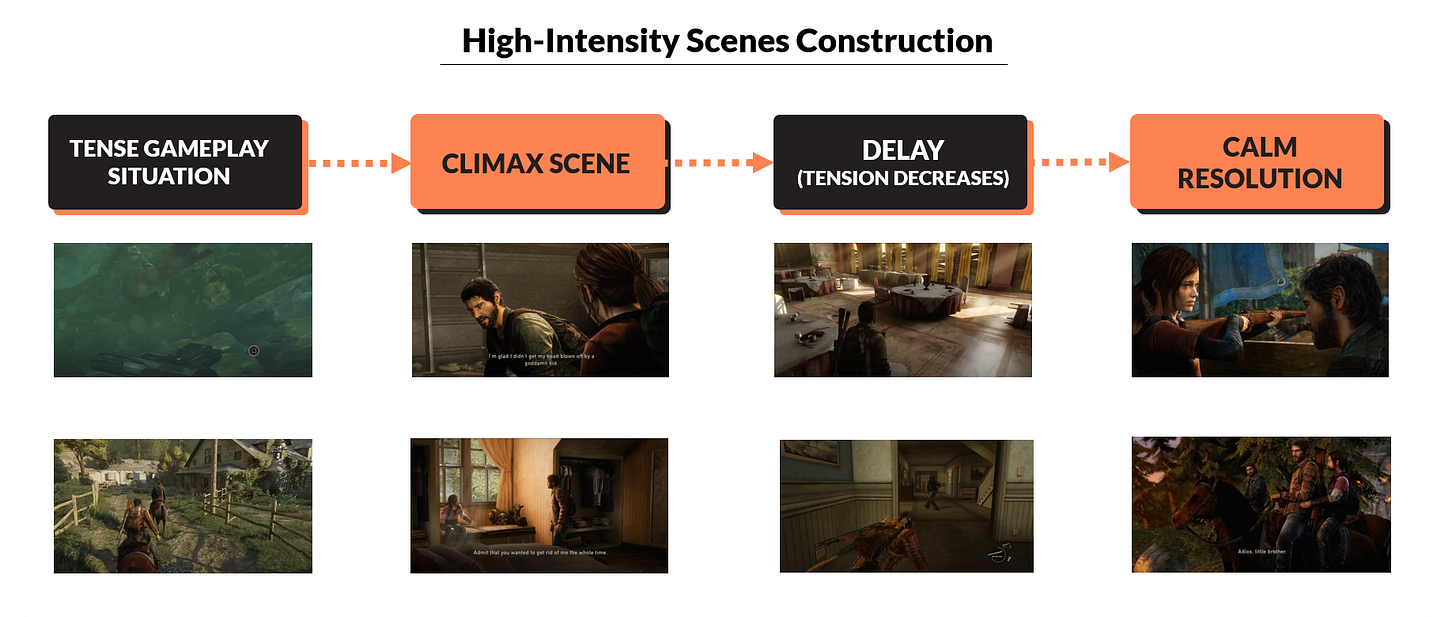

Joel, as the protagonist, undergoes the most dramatic evolution throughout the journey, and we notice a clever pattern from Naughty Dog: a dangerous (playable) situation leads to a climactic scene (not always playable) such as a QTE or a tense dialogue, then a pause. At this moment, the incertitude is still high, the suspense is unbearable, until finally we have a resolution with a calmer discussion & Joel (secretly) re-evaluating its choices.

Specific game events are always the catalyst for the character’s change: their impact is increased by holding on to the tension just a little longer. Again, I do not deny the quality of the art, the acting & realisation, but it’d be for nothing without the expertise in scene construction.

Structuring the Plot: Expectations & Surprises

We’re slowly getting to the biggest chunks of the story: sequences, or the subtle art of arranging all your nice characters, scenes & conflicts in a coherent order that maximises emotional impact. In The Last of Us, there are 11 sequences (or slightly less, depending on how we count): after the introduction, all of them follow the same structure of a mini story-within-the-story.

We first have an initial situation, which establishes the baseline for the characters: how are they feeling and interacting with one another? They have an objective that sounds simple enough, but quickly, there is a big event that raises the tension and changes the paradigm. After that, several complications may happen until a resolution is found, putting Joel & Ellie back on track.

Each sequence puts its twist to avoid the feeling of an “episodic formula”. For instance, the Pittsburgh sequence is longer to let the game breathe and slowly builds the characters scene after scene. The penultimate sequence in Salt Lake City starts particularly slow as if the game didn’t want to reach its conclusion, mirroring Joel’s feelings.

All sequences have the same goal of providing us with meaningful variations on the themes. While the main story only loosely connects the dots, most of the character’s evolution comes from these side story arches: Tess, Bill & Henry each depict an aspect of this violent world and serve as a cautionary tale for Joel, who doesn’t want to suffer the same fate. The arrival & departure of side characters provide major turning points which shake the status quo frequently and keep the story fascinating in the long term. I could explain how each sequence works, but you get the point.

Another McKee lesson I’d like to touch on is the importance of respecting the audience by giving them what they want, but not the way they think. When we start the game, we know that Joel & Ellie will end up bonding; there is no suspense there: what hooks us is how their relationship unfolds, the surprising low & high moments that stick with us. And Naughty Dog knows that: they purposedly lied in pre-release interviews to keep the secret on playing Ellie or the giraffe moment. They are masters of their craft.

Final Words

If Robert McKee’s work influenced Naughty Dog a lot, I’d also like to thank Neil Druckman & the team for openly discussing their craft. Video game creators are (arguably) often scared of talking about the behind-the-scenes. Yet, for The Last of Us in particular, we have incredible books & podcasts that give great insights on how to conceive a story that works on an emotional level.

Does peeking behind the curtain kill the magic? For me, and probably for you if you read this article, it never will: understanding all the work that goes into creating these experiences inspires me and the talent behind the blockbuster’s money-printing machine.

If you liked the topic of this article, I’m sure you’d also enjoy this one:

Really love this piece. Great work.

Now as designer how do you weave an engaging gameplay that serves the game narration and the different beats?

The sequences help serve the actual storytelling but how can it serve gameplay and vice versa?

Would love to have your opinion on this.

Allies mechanic that you lose, well Final Fantasy 7 did it with Arys. It sucks losing an important character so the emotional impact is there for the player for sure.

You might not necessarily need to introduce a new mechanic at every story beat otherwise throughout a whole campaign you might never be able to fully enjoy or explore the depth of the whole gamut of these mechanics. I know you didn’t say this it’s me thinking out loud :).

You can repurpose mechanics in some every 3-4 beats to keep players on edge for instance.

Anyhow enjoying greatly your pots. Thank you