The Unfair Lie That Ruined Demos

What could go wrong if I misinterpret data to make a shocking argument?

Many game developers believe demos hurt sales, yet none can tell why.

I can't remember the first time I heard this “fact”, probably on a forum or during my game studies. All I know is that I just accepted it. It felt a bit sad because, like everyone, I grew up playing so many demos for games I never intended to buy. In a way, it felt like exploiting the system, feeding my insatiable hunger for fresh content while saving money for the bigger fishes. It's not worse than piracy, for sure, but it somehow didn't feel morally right. And that's probably why I easily accepted the idea that “demos hurt sales”.

But it was a lie.

Or, at least, it was a claim made without strong supporting evidence. For this weird reason, what was a staple of video game marketing faded out for years. To this day, some developers keep believing that demos negatively impact games, even when current-day data says otherwise.

In this issue of The Arcade Artificer, we're debunking an old myth, examining its origin and trying to understand why it stuck. In a future article, we'll see why demos are crucial again and how to design them, so feel free to subscribe!

An Inspirational Speech Full of Approximations

I was first exposed to this story by reading this great article from game developer & marketer Tavrox titled “The Game Conference That Cursed Demos for 6 years”. It immediately made me want to dig deeper, and I wasn't disappointed by what I found.

Before going further, just a quick note: in this article, whenever I use the term “demo”, I only mean “consumer-facing demos”, not internal prototypes or vertical slices used to pitch to other industry professionals (publishers, journalists, etc.)

With this clarification out of the way, we can introduce the protagonist of our story: Jesse Schell. You may be familiar with the name of this American game designer & teacher thanks to his best-selling book The Art of Game Design, one of the genre's earliest (and arguably still among the best). Jesse worked at Disney & founded his company, where he serves as a CEO, and he used to give a lot of conferences.

The specific talk we're interested in today was part of the DICE Summit 2013. Mysteriously titled “The Secret Mechanism”, the 20 minutes keynote covers a wide variety of topics sharing the common theme of “things aren't always the way they seem”. Schell makes funny remarks about how he wrongly predicted that iPad was useless and would flop. He also talks about how humans are biased regarding pricing & discounts. There's a lot of vaguely inspirational stuff in there, but the guy certainly has a talent for captivating audiences (I learned while researching for this article that he's also a circus artist & comedian, which explains his talent on stage).

After making a point about how seeing someone wear cool cosmetics in MMO ignites your desire to own the same piece of customization, he jumps to a graph with several Xbox 360 game sales curves. Time slows down as Schell dramatically reveals how games with only a trailer sell 2.5x better than a game with both a trailer and a demo. Boom. Everyone's shocked.

He then elaborates with the following argument: when you see a trailer, you make a plan to play the game (like with MMO cosmetics); therefore, not having a demo available means you have to buy it.

We won't have much more information since Schell switches to yet another topic. Still, it was enough to generate many articles in the press, which were promptly discussed on gaming forums afterwards.

Journalists should have dug further into Schell's source because they would have realized the story was five years old already.

Where does the data come from?

So, below the graph Jesse Schell shows, there's the mention “Data courtesy EEDAR via Geoff Atkin”. EEDAR is a research firm co-founded by Mr Atkin which specializes in collecting factual data on video games: camera type, protagonist genre, presence of multiplayer mode or not, etc.

By collecting only verifiable facts, they could claim that their database & statistical analysis was purely objective. However, EEDAR still crossed their data findings with other industry analyst companies, such as the NPD Group, which specializes in estimating game sales for North America. Estimating physical sales & revenues is a notoriously tricky task (and even more so on a global scale), leading to potentially wide margins of error.

Like Jesse Schell, Geoff Atkin gave lots of conferences, including one in GDC 2013 titled “Awesome Video Game Data”, which provides several insights on the state of the game industry, yet this crucial information about the negative impact of demos on game sales is missing. Why?

With more Google Search, I discovered that the graph shown by Jesse Schell at DICE 2013 comes from a 2008 talk given by EEDAR at MI6, another professional event specializing in game marketing. Unfortunately, we don't have any video recording on the internet, but by searching “EEDAR MI6 2008”, we find another bunch of press articles relaying the news that “demos can hurt sales”. It's cool because now we can retrieve the same graph but for PS3 game sales, and it already tells a different story: the differences between the groups aren't as impressive.

But more importantly, now that we know that the data was presented in early 2008, and therefore regroups games released up to the end of 2007.

Firstly, in 2007, Youtube was starting out: the most popular game trailers only had a few hundred thousand views, which is negligible compared to today. People watched trailers in other places (such as gaming websites), but it was a lot less prevalent than today. Trailers were reserved for a certain elite who could afford them with their high marketing budget (for TV & store ads, to show to journalists at E3, etc.) And as Geoff Atkin explains himself in his conference, a bigger marketing budget correlates with higher sales.

Secondly, 2007 was the beginning of the generation, and relatively few games were available then. According to Wikipedia's list of all Xbox 360 games, there were more than 200 games released physically in North America (NPD didn't track digital sales at the time). This is a small sample size, even more so when we split games again into four categories: a few outliers can have a massive impact on the data.

One of these outliers is Halo 3. That game was such a hit when it came out that it reportedly sold close to 4 million in its first month on US soil alone. Thanks to its extraordinary sales, Halo 3 can make the whole group of games “with a trailer but no demo” looks like they sell 2.5x better on average. In reality, for all we know, there could be 25 games that sold 100k copies (the same as the “trailer + demo” cluster) and adding Halo to the group would be enough to raise the average to 250k.

And Halo 3 wasn't the only candidate susceptible to influence sales: Call of Duty 4 or Guitar Hero were also big hits of that year which didn't have a demo. So what happens in years without such hits? Or, more interestingly: what could the story be if those hits had a demo? According to the Xbox 360 marketplace, there are 90 demos for games released pre-2008; therefore, if Halo 3 had one, it would be enough to raise the average of this entire group by 45k copies.

You see the problem with using data to tell a story: what you want to say (" games without a demo sell better because people have no choice”) may absolutely not be the story behind the numbers (" a few hits without demos skewed the whole group's average”).

The Difference Between Correlation and Causation

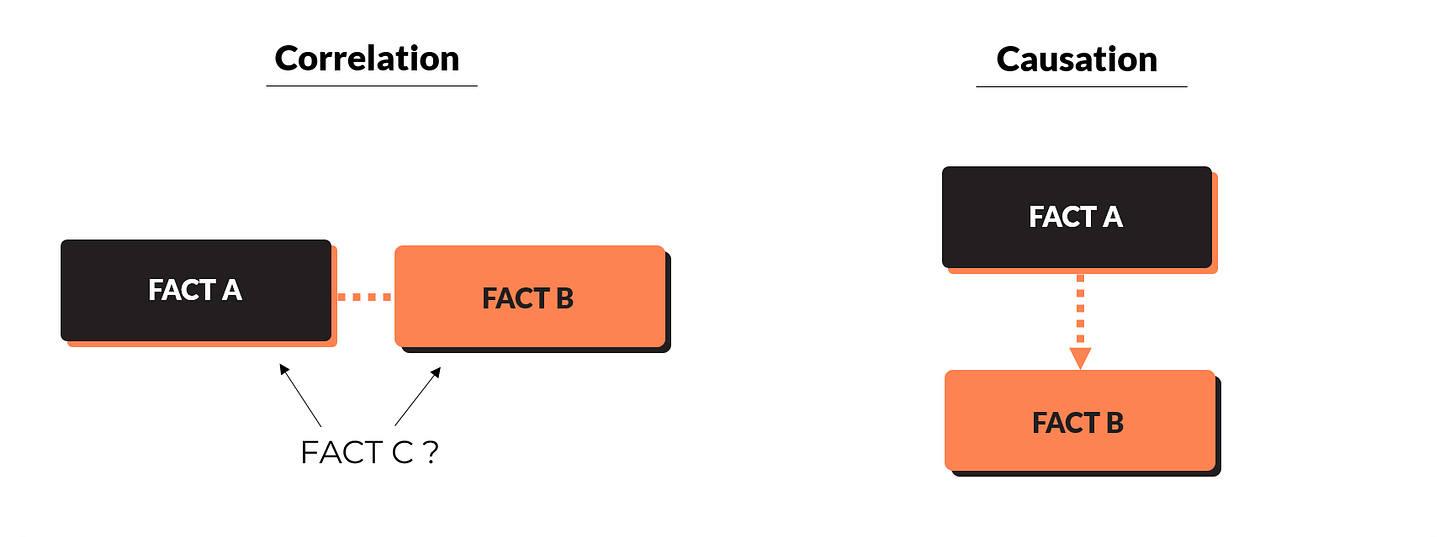

I'd speculate that EEDAR had stopped mentioning these findings by 2013 precisely because the data was five years old, and they couldn't replicate the results again. But there's a bigger problem still: the issue with mixing correlation & causation.

They were partly aware of the issue since an article from 2008 was written to point out the logic's flaws, with a reader mentioning that big games with high anticipation & high marketing don't need demos anyway. EEDAR's co-founders answered "Causation is a hard thing. There are so many variables in the industry. What works now may not work later on causing something. What we want to do is point out really strong correlations".

And the quote continues "If you have a game with a $100 million marketing budget, you probably don't need to release a demo. What our evidence showed us was, if you only have an average game and an average marketing budget, putting out a demo that's bad is going to hurt you even more than [if it] were a triple A title [where] marketing might make up for it.”

It's an entirely different story!

Did the misinformation influence the industry, though? Maybe, but since demos didn't disappear overnight, that should probably have raised questions in people's minds: if demos had a negative impact on sales, why would Activision, Warner, Capcom, EA, Sony & others continue to make some? Not to mention the elephant in the room: what about PC, where players often use demos to check if the game runs on their computers?

We must not forget that creating a solid demo can be arduous since you have little playtime to prove the game's quality, and you can't afford to waste it on tutorials & story exposition. Furthermore, with games getting more open, complex, and online-based, demos became harder to produce in the 2010s, so if it wasn't going to be a decisive marketing factor, that time was better invested in polishing & debugging, for instance. So maybe not making a demo was the right choice, even if the justification is incorrect.

Conclusion

In my game design career, I can't count the number of times some higher-ups had questionable interpretations of poorly contextualized data. It takes time to develop the reflex to take a step back & question if the causation we think we see (because we're human, we make links) is real or if we're missing the actual correlation.

Many people would love to figure out the secret to selling more games, but it's impossible: every game is unique, there are thousands of factors that go into their success/failures and without a time/multiverse machine, we can never measure the impact of each decision. So, always be suspicious of people claiming they've found the secret (especially if they don't use it for themselves).

If you liked the topic of this article, I’m sure you’d also enjoy this one:

Nobody Would Copy the Nemesis System Anyway

Few games in history simultaneously receive the titles of « uninspired ripoffs » and « innovation of the decade ». In 2014, when Monolith Software announced its new game Shadow of Mordor, people quickly labelled it "Assassin's Creed in the Tolkien universe”. Fortunately, the game had a trick in its sleeve, the “Nemesis system”.