Marvel Champions and the Superhero Dilemma

How veteran designers craft powerful choices

Is making a good adaptation easier or harder than an original game?

On the one hand, rich lore can be a blessing to start on the right foot and get your creativity rolling. On the other hand, the source material may become a curse if it adds more constraints than opportunities. Making an adaptation is often a double-edged sword: when you succeed, you simultaneously catch fans and newcomers alike, but if you fail, you lose both.

Fantasy Flight Games is a company which made its speciality of translating popular franchises into great board games. After many successes with Star Wars, Lords of the Rings & more, it took three veteran designers of the company to imagine Marvel Champions, a brilliant card game which captures the superhero fantasy like no game before.

I wouldn’t call myself a Marvel fan, I’ve barely seen the movies and never read a comic, but I would gladly accept the label of Marvel Champions fan as this game inspires me as a designer as much as it entertains me as a player. As you’ll discover throughout this issue of The Arcade Artificer, the genius of this game lies in the recreation of the captivating dilemmas that a superhero faces.

A Great Power Implies Great Responsibilities

Marvel Champions is a typical “coop firefighting” experience, a board game sub-genre in which players must manage various threats while trying to accomplish a winning objective. I already explained a lot about the strengths of this design structure in my analysis of Pandemic, and Marvel Champions adds even more depth and nuances to it.

Each scenario pits the player(s) against a villain: their goal is to lower his hit points to zero and prevent him from killing the hereoes. That’s a typical boss battle setup so far, but here’s the twist: there is a second objective called the “main scheme”. This card is placed alongside the villain during the setup and will represent its mischief. As the game progresses, various effects add “scheme points,” and players lose immediately if their total reaches the indicated threshold.

Duality is at the core of Marvel Champions, and to mirror the two ways the villains can win, the designers propose a relatively uncommon choice for a superhero game: deciding which persona you want to be. Indeed, each identity card has two sides: one for the hero (Spiderman) and one for the alter ego(Peter Parker). You may flip only once a turn, and you’d better choose carefully since each side influences what the player & the villain can do during the turn.

In hero mode, you have the most options: you can decide to attack, thwart (remove scheme points), or defend, but during their turn, the enemy will attack you.

In alter ego, you can only select the recovery (healing), which is often necessary to avoid dying, and the enemy won’t attack, but they will instead add even more scheme points (while you’re away, they’re furthering their evil plans!). Many cards are also restricted to a specific side which may influence your decision to flip to hero or alter ego.

Having two problems to manage at once and giving the player the opportunity to “pick his poison” is a great idea to generate tension.

And Then Came The Cards

Indeed flipping your identity & deciding how to juggle between the objectives is integral to your winning strategy, but of course, most of the variety & opportunity for optimisation comes from how you use your cards.

So, another distinctive mechanic of Marvel Champions is how you pay the cost of your cards by discarding others from your hands. If a card costs two, you have to discard any two cards from your hand to be able to play it. In a typical hand of five or six, you may therefore play 1 or 2 card a turn, sometimes 3, which makes for difficult dilemmas again.

This rule has several advantages compared to dedicated resources cards (as in Magic The Gathering or Pokemon), or even automatic resources (as in Hearthstone).

First, it lessens the problem of “dead cards”: what you can’t play now can always be discarded in favour of others. On the contrary, it adds a meaningful layer to your choice: “I’d love to keep this card for later, but I have to discard something now to play that other one”.

Second, playing (& discarding) lots of cards every turn also help to cycle through your whole deck faster: unlike games where you draw one card at a time, you refill your full hand each turn in Marvel Champions. Thus, it reduces the frustrating scenario of not getting the key upgrades or combo pieces of your deck.

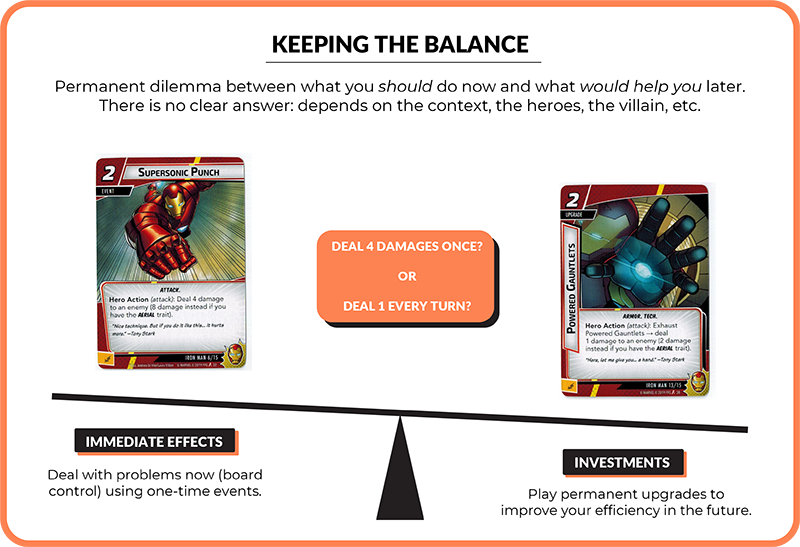

And finally, of course, it reinforces the theme of the superhero dilemma. When looking at your hand and strategising your turn, you frequently have to choose between one-time effects to address immediate problems and permanent upgrades, which are weaker but whose effect compound in the long term. The later is technically more efficient, but if you lose shortly, it’s useless.

Like the double loss condition & the dual identity card, these two possibility to use cards increases the strengths of choices players and nuances of the options. The -right- choice doesn’t exist, it’s contextual, and the context is ever-changing.

Breaking the Monotony

As explained earlier, players have some control over how the villain activates (attack hero, scheme against alter ego) and the threat they’ll face. But however clever they want the players to feel, the designers didn’t want the game to be a math puzzle, so they had to introduce a part of unpredictability.

In Marvel Champions, the randomness comes from the villain’s deck, built with specific encounter cards with -again- two purposes.

Each time the villain attacks or schemes, you draw an encounter card and add the boost icons to the villain’s printed attack/scheme value. There can be anywhere between zero & three, and sometimes an extra effect, which spices everything up with an ingredient of luck. Boosts are rarely decisive, and it’s OK, they’re not meant to throw the strategy away, just to add variance.

Every player also draws an encounter card per turn; this time, the disruptions can be much more significant. These come in all sorts of sizes & shapes, as far as the designer’s imagination goes, which we can sort into two categories: immediate effects and additional problems.

The immediate ones are, of course, annoying & disrupting your plans since you’ll need to adjust your next turn accordingly (for instance, heal the extra damages you couldn’t anticipate). On the other hand, the permanent cards add a malus as long as they’re in play and therefore come with a difficult dilemma: should you deal with them now or endure the effects? You may not have efficient solutions to these new problems, and remember you still have the permanent risks of losing to address (all that with limited resources).

Breaking the monotony is also about providing tension peaks, and there’s no better example in Marvel Champions than the Nemesis mechanic. Each hero has a special set of encounter cards, called the “Nemesis set”, which may come into play only if you draw a specific encounter card. The consequences are terrible, as it directly adds one powerful minion and a side scheme designed to counter your hero’s strengths!

Statistically, the Nemesis isn’t that frequent, there is a good chance you don’t see it in the majority of your games, but if it comes, you’re in for a tough time!

Is this balanced & fair? Not at all, but in a PvE game, the alternation of small & big obstacles, predictable or surprising, makes the game stimulating and, therefore, fun.

Conclusion

To get back to the initial question, Marvel Champions makes the work of adaptation effortless simply because it captures so well the strengths of the superhero fantasy: it’s not a pure power trip, what we love about these characters is the struggle they face between their human & heroic duties.

To successfully translate a fantasy into an engaging interactive experience, you can’t stick to its surface look & feel, you have to dig deeper and identify its strongest choices. Picking between attacks A & B will never give you the same emotions as a dilemma between saving MJ & saving the city of New York.

If you liked the topic of this article, I’m sure you’d also enjoy this one: