The Game Design of Tour de France

A look at how one of the biggest sport competition is continuously tweaked to create the most interesting challenge

This year’s edition of Tour de France has just ended, with Jonas Vingegaard winning a second title in a row, and here I am, scrambling to write this issue because I genuinely believe it’s a great topic to cover in a game design newsletter.

I wasn’t a fan of the Tour when I was younger, I thought it was the most boring way to waste summer afternoons. Now that I discovered you don’t have to -actually- watch the whole thing, I’m really into it: watching the key moments is sufficient to understand everything that’s going on in this fantastic three-week race.

Like any other sport (and e-sport), there are fascinating storylines regarding the riders, with underdogs, favourites, underwhelming results & surprising victories. However, this format of cycling race (le Tour, Giro & Vuelta) is also a unique game worth studying: which rules are in place to keep the competition fresh & exciting for riders & spectators? Which strategies emerge, and how do designers respond?

In this issue, I’m giving you the keys to understanding the game of Tour de France and how its design evolved over time.

Cycling Basics & Break Formation

The Tour de France is, first & foremost, an endurance race, with about 3500 km split into 21 stages over the course of three weeks. The pacing is relentless; riders have an average speed above 40 km/h (despite climbing many mountains). About 20% of riders abandon the Tour before the end, either after an injury or because they get eliminated for not making it to a stage finish within the maximum allowed delay (usually around 40 minutes after the winner of that stage).

On the road, riders have a supporting staff to give them water & food, as well as team cars following them to assist in case of mechanical or medical issues. It ensures they’re in the best condition, ready to spend their whole energy fighting against two main forces of nature: air friction & gravity.

Drag (or fluid resistance) is the physical reason why cycling is a team sport: when you ride close to one another, the cyclists in the back are protected from air and spend up to 40% less energy. All stage long, you’ll see riders relay at the front of the peloton to pull for a few minutes, then rest while someone else takes the spot.

Sometimes, a group accelerates to form a “breakaway” and get ahead. If you don’t know about the sport, it may sound like they’ve got a much better chance of winning, but the reality is more nuanced: the break riders need to make more efforts to maintain the gap, especially if they’re only a few in the group with limited possibility to relay. A cooperating peloton will always be able to control the gap & close it eventually, like in stage 7 this year when Pierre Latour went in the break 80 km before the finish, only to get caught 5 km from the end.

However, you have to keep in mind the peloton isn’t a single hive mind: there are actually teams in direct competitions here, and they face dilemmas that fall in the realm of game theory. If you spend all your energy at the front of the peloton to catch up with the break, then the riders who were patiently waiting behind will beat you on the final sprint. The same thing happens in the breakaway, and you will often see them slowing down drastically near the finish line, sometimes to the point they get caught, just because they don’t want to be the person who made all those efforts only to help a competitor win.

Cycling involves a lot of strategies, bluffing, opportunistic alliances & betrayals.

The General Classification and How to Win the Tour

Breakaways may also happen in mountain stages, but it’s completely different. Since air friction isn’t as important as gravity in steep slopes, the peloton doesn’t have an edge: what matters more is the individual effort. Mountain stages are the most important of the Tour since this is where the best riders gain time on their opponent in the general classification, whose leader wears the famous Maillot Jaune.

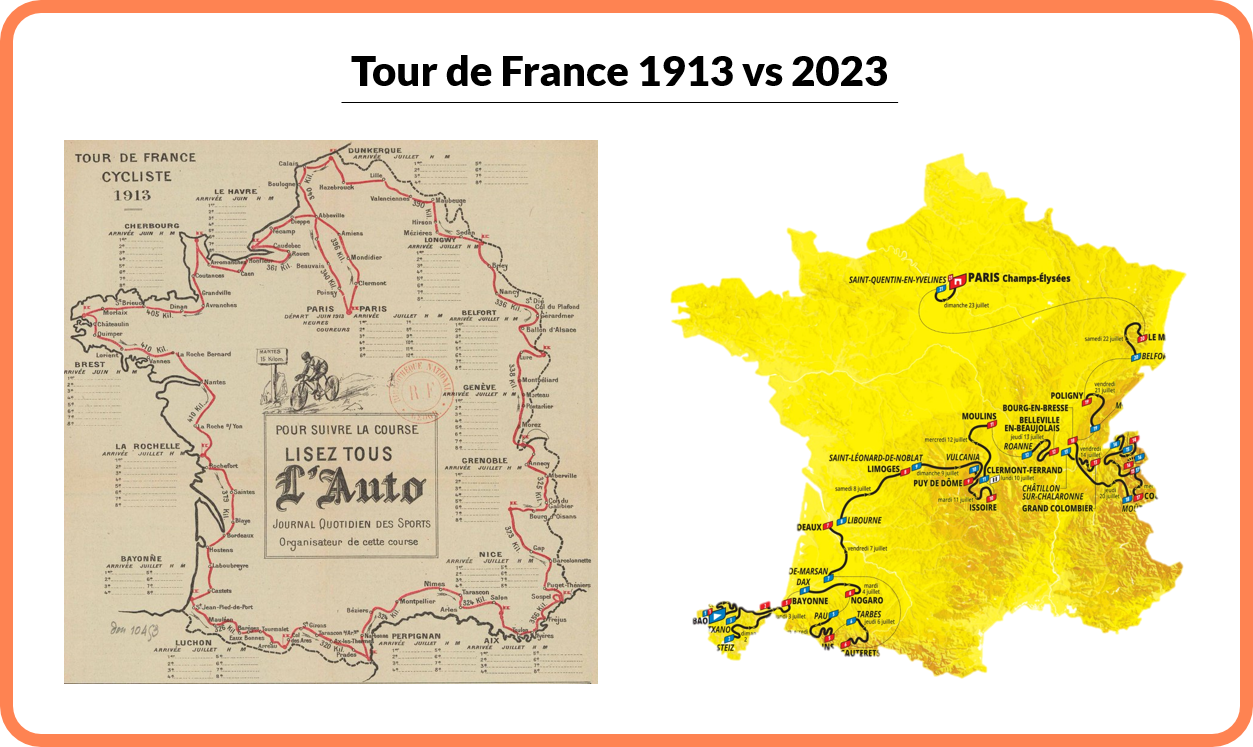

This is why the Tour de France doesn’t follow along the coasts & frontiers like the first editions but instead always goes through the Alps & Pyrenees, where the highest climbs are located. Mountains are the key stages, so the course designer ensures these happen during weekends (when most spectators are watching). Thierry Gouvenou, the race director, works all year long to design an ideal route that’ll give the best spectacle, juggling with many constraints & figuring a way to make it as diverse as possible, like a level designer would.

How do you win the Tour then? Well, it’s a team effort. Several teams revolve entirely around a leader who has a fair shot at the general classification, and seven mates riders will do everything to preserve their “leader” for 95% of the race for him to have the most energy in the challenging climbs. In this year’s edition, we had a clear duel between reigning champion Jonas Vingegaard & previous runner-up - and winner in 2020 & 2021- Tadej Pogacar, but a bunch of other teams were also going for general classification & aiming at the podium.

In the flat or hilly stages, teammates pay attention to the riders who get in the break and will chase immediately if a direct competitor tries to go for it (which is known as “defending” or “controlling”). Riders who are allowed to get in the breakaway usually lag far behind in the classification.

In such an environment, crashing is almost the bigger threat; hence you’ll often see the GC leaders ride at the front to limit the risk, even if they don’t really want to sprint for that stage. There are bonus seconds to gain at specific checkpoints to spice things up, and it could almost have decided the Tour this year since the two favourites were less than 10 seconds apart at the end of the second week.

In the mountain, teammates are still essential to set the pace, motivate you & help ride downhill, but the individual effort is the only thing that matters in the end. We’ve seen it in the particular time trial of stage 16, where the best two dominated the others completely. The gap between Vingegaard & Pogacar was already almost impossible to catch up, then it got even worse in the following stage, where he lost five more minutes. In an endurance race, you’re one bad day away from losing. Pogacar finishes second in the Tour again, claiming the White jersey (awarded to the best rider under 25 years old) for the fourth time.

The Games Within the Game

There are 176 riders in the peloton at the start, but only one Maillot Jaune for the best overall time, and very few teams/riders capable of contending, so what do the others do?

First, winning a stage on the Tour de France is also very prestigious, and it often comes down to having the right team tactics or getting in the breakaways (as explained in the first part). On the flat finishes, when the peloton is likely to arrive as a group, the best candidates for stage wins are the “sprinters”, a category of riders capable of short bursts of massive efforts.

As you can imagine, your chances increase drastically if you are in the front of the peloton in the final kilometre and if you can have a teammate riding in front of you to save your energy until the last second. The best sprinter this Tour was Jasper Philipsen, who won four stages & came second twice. He’s a skilled sprinter and had the best teammate in the category, Mathieu Van Der Poel.

Sprinters are also ranked on the “points classification”, a separate ranking system whose leader wears the Green jersey. The first 15 riders to cross the line each day score points, and there are intermediate sprints throughout the race to incentivize early efforts & competition (rather than saving it all only for the finish). It’s interesting to note that the balancing has evolved: the points for intermediate sprints have increased a lot since 2011, and the flat finishes give more than mountains to make it almost impossible for non-sprinters to “accidentally” win the Green jersey.

Something similar happened to the other particular ranking, the mountain classification, whose winner wears the Polka dot jersey. In the 1990s, riders would complain that the scoring system encouraged riders who go for early breakaways to grab points in the first climbs of the stage, thus ranking high there without actually being the best climbers at the Tour (which, as explained previously, are normally the same people who win the General Classification). This led the organization to tweak the points awarded: less for smaller climbs & double the points for climbs near the end of the race.

Funnily enough, this caused the opposite problem: the winners of the general kinda “automatically” won the Mountain classification. For instance, in 2021, Tadej Pogacar won with 107 points, 80 of which came from winning two stages in the Pyrenees. Sure, he was the best climber, but for 2022 the organization decided to cancel the “double points” rule. This incentivized other good climbers to animate the race, and the new balancing paid off: in 2023, Giulio Ciccone made it his goal, collected points on many occasions, and eventually won it (despite finishing 32nd on general classification). The Tour may be at its 110th edition, but it continues to receive updates to stay fresh & exciting.

Conclusion

There are many more topics worth digging into, but you get the point. It’s fascinating to me how, even in such a large-scale game, the organizers play a significant role in designing & adjusting the rules to keep the challenge interesting for people to watch & for riders to compete.

One last fun fact: did you know that some riders were purposedly going slower to be ranked at the last place since it was an excellent way to stand out for the public and could lead to invitations to more races afterwards? The organizers didn’t like it much, so in 1939, 1948 & 1980 had a special rule to eliminate the last riders at the end of some stages. No matter the game, players will find a sneaky way to optimize the fun out of it!

If you liked the topic of this article, I’m sure you’d also enjoy this one:

The Unfair Lie That Ruined Demos

Many game developers believe demos hurt sales, yet none can tell why. I can't remember the first time I heard this “fact”, probably on a forum or during my game studies. All I know is that I just accepted it. It felt a bit sad because, like everyone, I grew up playing so many demos for games I never intended to buy. In a way, it felt like exploiting the …

Very good article, i never watch the Tour De France, i don't get the point of the competition at all but with this article now i understand it better ! It's very cool to see the update they made to keep it fresh